Non-Narrative Comics

About this Issue

What connects two panels placed side by side? The default answer, more often than not, is ›narrative.‹ Scott McCloud, for one, calls for an unravelling of the »[m]ysteries surrounding the invisible art of comics storytelling« (74). Issue #8 of CLOSURE contests this narrative reduction and uncovers a non-narrative art of comics beyond storytelling. From a variety of perspectives, our articles show how comics subtract narrative, withhold closure, stall storytelling – and theorize the unfamiliar formal, abstract, nonfictional or poetic constellations that emerge as a result. »Must Narrative Be Renounced?« (Groensteen, 174) Our contributors experimentally answer ›yes‹ to this question and outline the logical, affective, designed connections that emerge in place of narrative.

Although our issue investigates non-narrative comics beyond the diegetic, beyond sequence, or beyond character, it is not solely dedicated to the absence of familiar modes of storytelling. Rather, we ask about the reservoir of possibilities obscured by the notion of an eventful, narrative-inducing change of state knitting together dispersed panels. ›Abstraction,‹ particularly, makes itself felt once the continuity of drawn characters and their spatio-temporal development is suspended. However, rather than a subgenre of ›abstract comics‹ deliberately poised at the experimental limits of the medium, non-narrative can be explored as an affordance that always already undergirds comics forms. From this angle, non-narrative is a substrate, a potential for story-suspension that exploits the basic building blocks of comics: their double perspective on sequence and layout; their braiding of dissimilar signs; their changeable distribution of textual and visual elements; their marks on the page that do not have to coalesce into narrative worlds. This movement »beyond the diegetic and the narrative« (Molotiu, 87) finds prototypical expression in abstract and experimental comics, yet is not exhausted by them. Consequently, our articles also locate the possibility of non-narrative in the margins of popular storyworlds and propulsive plots.

Our contributors trace the function of panels and signs unmoored from sequential, linear, or episodic modes of storytelling. Such non-narrative potential requires a reconsideration of the form of comics as much as an attention to the materiality of the medium. Once the plot is backgrounded, what emerges in its stead is »the attention to surface, the deemphasis on linear sequence, the move towards abstraction« (Bukatman, 113). Further, our »critical re-thinking« (Baetens, 104) of comics entails replacing degrees of narrativity with degrees of abstraction. Which alternative logics are laid bare by a move beyond narrative coherence? Which »coherent mental model« (Kukkonen, 12) do readers infer once narrativity falls by the wayside? Which diagrammatic, abstract, tabular, static, conceptual models accompany our graphic reading, viewing, and knowing beyond narrative?

Finally, the function of non-narrative is not exhausted by a formalist revision of the mediality of comics. There is a method to the non-story, a function undergirding both an artist’s quest for deliberate non-narrative expression and a reader’s attempt to discover a non-narrative potential below the event-rich surface of a comics potboiler. After all, if »the business of living well is, for many, a completely non-narrative project« (Strawson, 448), can we analogously understand the business of viewing comics well as a storyless concern? Along such lines, our contributors show that representation without and beyond narrative allows for the emergence of revolutionary temporalities (Aramburú-Villavisencio), a medium-specific treatment of the disruptive afterlives of trauma (Hindrichsen), or a turn to everyday occurrences (Picado/Senna/Schneider). Non-narrative, then, is neither non-political nor non-functional, but intimately connected to cultural negotiations of power, class, and gender. The experiences and affects that our authors trace throughout a variety of comics at the borders of narrative can appear too unruly to be encompassed by narratives, in particular by any linear succession of changes of state. Their formal equivalent is a hitch in the smooth unfolding of the plot, or an emblem that dislodges itself from well-worn narrative scripts.

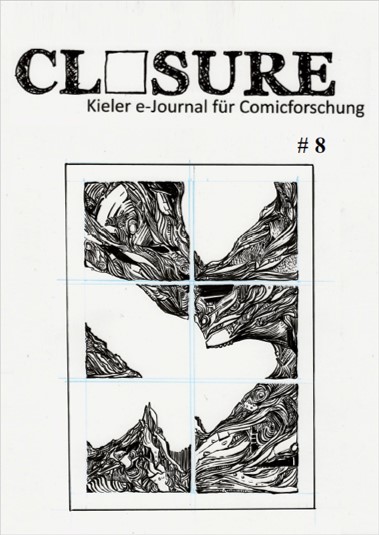

Rather than the absence of narrativity, our contributors bring out the presence of comics features beyond sequence: the material(ity), colours, lines, sound effects, symbols, design, diagrams, performativities, gestures, the sheer simultaneity of signs that come to the fore once we suspend the question ›what happens next.‹ CLOSURE #8 considers comics beyond narrative norms in order to explore the forms and functions of a new, abstract world in the shell of the old. Who better to lead us into this uncharted abstract environment than comic artist Gareth A. Hopkins? Hopkins’ art has long since revolved around the expressive possibilities of abstract sequential art. For our cover, he has contributed an abstract landscape comic that appears to be segmented into panels. But not all of the boxes contribute to the coherent mass: the bottom panels appear misaligned, out of sync – a breach in the representational order that makes us reconsider the consistency of the whole.

Such tensions between order and collapse also animate the comic that Hopkins has created for this issue. Initially, his double-page spreads establish a pattern of intermingling colours on the left side and stark black-and-white shapes on the right. The latter appear as organic, swirling forms either emerging from a grey background or being eclipsed by it. This stark opposition, however, changes on the fourth page of Hopkins’ comic: suddenly, the panels are intercut as diagonal, triangular sequences traverse both pages. Amidst this panel trouble and its aftermath, it becomes clear that abstract comics can create rhythms, movement, forms of order, and jarring breach, a visual eventfulness that cannot be encapsulated by any one story.

In his third contribution to this issue – his mixed-media »Closure Process Comic« – Hopkins takes us through the creation of his sequences. His »non-abstract comic« about making abstract comics becomes a study in contingency and decision. Geometrical plotting of panel layouts is interrupted by bursts of painting over existing shapes. Hopkins’ meta-comic is a study in accidents and an appeal to allow them to happen, follow their trajectory, and integrate them into the creative process. On the one hand, the artist offers a compelling narrative of artistic creation and thought with comics (rather than only about them). On the other hand, the possibilities of this medium once more are not exhausted by a linear story, let alone an easily followed how-to guide. Rather, the artist’s decision process suggests a non-narrative kernel, an engagement with materials and environments that exceeds a straightforward plot.

Instead of hard-and-fast distinctions, comics exhibit mixed zones, in which we can – but by no means must – recover stories. In this vein, Jan Baetens’ systematic approach to non-narrative in comics and beyond demonstrates that we would do well to consider the ›contrary axis‹ of the narrative/non-narrative relation. On this changeable scale, an exclusive either-or categorisation is replaced with a gradient of narrativity. As Baetens shows in his article »Non-narrative or noncomics? (with some notes on Holz by Olivier Deprez and Roby Comblain)« it is possible for a comic to be »both at the same time.« Baetens demonstrates that any statements regarding the essentially non-narrative status of comics are bound to fail, as is any default identification of abstraction with a suspension of storytelling. What emerges from Baetens’ subtle differentiation is ›non-narrative‹ as a negotiable property open to interpretation and context-sensitive negotiation. Instead of a tag applied with taxonomic certainty, his scheme of more-or-less intense ascriptions of narrative allows us to diversify the ways in which we encounter alternatives to storytelling – up to and including such phenomena as »narrative running out of steam.« The advantages of Baetens’ refusal of media essentialism come to the fore in his presentation of Oliver Deprez’s ›noncomic‹ practices in Holz. The ›non‹ in ›nonnarrative‹ becomes multistable in Baetens’ account, and its discovery an exhilarating occasion for a redistribution of the processes and materialities we ordinarily associate with the comics medium.

What is the function of such contestations of narrativity? What does a focus on non-narrative allow us to see? Andrea Aramburú Villavisencio’s contribution discusses Waiting (2018) by comics artist Adriana Lozano Román, which collects portraits of women who seem unhappy. Picking up on Sara Ahmed’s concept of the ›good life,‹ the author traces how the comic exploits the flatness of the page to spatialize the allegedly temporal process of waiting. Aramburú Villavisencio observes that Lozano’s comic imitates an aesthetics reminiscent of 90s women’s magazines, and argues that the images produce an atmospheric tension but do not add to a narrative plot. Due to the absence of narrative, the recipient, who is confronted with portraits of reclining, resting women, becomes an ›unmoored reader‹ whose interpretation emerges from scanning the comics page in multiple directions. In her close reading of individual images, Aramburú Villavisencio reveals that the wait in Lozano’s comic can either be read as »endless and tedious« or celebrated for its revolutionary potential which »invites us to interpret rest as an intersubjective and embodied mode of thinking about women’s agency.«

In his contribution »Beyond the Chronotope: De-narrativization in Graphic Trauma Narratives (1980-2018),« Lorenz Hindrichsen also investigates the representational potential that opens up once narrative – particularly sequential narrative – is suspended. Specifically, he argues that individual and collective trauma revolves around an inexpressible kernel resistant to narrative expression. In the context of the temporal dispersal of traumatic experiences, attenuation of sequentiality emerges as mimetic. Specifically, the de-narrativization of »cultural, historical and biographical« temporalities mirrors the way in which the aftermath of violence cuts across all-too facile causal links between past and present. Trauma, after all, lingers, disrupts, and recasts the order of importance allotted to past injuries. Correspondingly, non-narrative breaches of story logic drive home the impossibility of simply narrating our way from crisis to resolution. Hindrichsen claims that instead of merely representing trauma, comic artists model how this emotional response functions, how it fragments memory, entangles the individual in patterns of repetition, and disrupts progressive arrows of time pointing ever-forward. Such derangement of stories by less-than-narrative forms can be »strategic,« refusing as it does any imperative to ›move on,‹ to leave the past behind. Comics-specific de-narrativization helps us understand that acknowledging trauma’s unruly resistance to story may be a first step towards granting the aftermath of distress its full representational, but also ethical, weight.

That comics can attenuate eventfulness does not necessarily entail the absence of narrative. As Benjamim Picado, João Senna and Greice Schneider show in their contribution »Comics, Non-narrativity, Non-Eventfulness: Three Examples from Brazil,« a more precise analysis may be derived if the category of ›intrigue‹ – narrative interest – is considered alongside narrativity. From this vantage point, the sense of a tightly interconnected plot can be productively dialed down in comics, without thereby relinquishing narrative per se. Picado, Senna and Schneider claim that this focus on the more-or-less intriguing nature of a panel arrangement opens up strategies of »differentiating ›low eventfulness‹ from strict ›non-narrativity.‹« This gradient, by extension, allows the authors to pinpoint the function of reduced intrigue in contemporary Brazilian comic strips. The cartoons in their case study evoke mundane moods by reorienting readers’ attention to tabularity or iteration, to a whole host of forms alongside the sequential. This thematic concern with the poetics of everyday life hinges on a variable sense of eventfulness without, however, doing away with narrative altogether. The article, then, can also be read as a proposal to complicate any hard-and-fast dichotomy between narrative and its non-narrative counterpart.

The meaning of non-narrative signs (and the non-narrative reading strategies unearthing them) analysed by Aramburú-Villavisencio, Hindrichsen as well as Picado, Senna, and Schneider should not be taken to be unambiguously, and essentially present. The inquiry into ›non-narrative‹ requires each and any seeming guarantor of narrativity to be put to the test. Case in point: In his article »Quasi-Figuren. Im Grenzbereich der Körperlichkeit,« Thierry Groensteen revisits the concept of the ›literary character.‹ He points out that traditional ideas of literary characters rely upon the reader’s willingness to identify with the latter (what he terms ›referential illusion‹). Yet, characters conceptualized on the page differ from those embodied by actors on stage or screen: a comic book character cannot be separated from its ›graphic code.‹ Groensteen discusses a variety of examples of minimalist comics which seek to create »a world of pure drawings without any anthropomorphic reference.« Amongst others, he shows that the miniaturized drawings of Maaike Hartjes and Lewis Trondheim scrutinize the concept of the literary character, and he explains why José Parrondo’s Eggman can still be considered a character although he does not seek to represent anything but the fact that he is an artificial drawing. Eventually, the author shows that even the ›realistically‹ conceptualized characters in Marion Fayolle’s comics foreground their paper qualities. Although all of the examples invent characters which highlight forms and their interaction with their (drawn) backgrounds, Groensteen concludes that our desire for narrative and the anthropological dimension makes us see characters in all kinds of shapes, forms, or dots.

In addition to our special section on non-narrative, the general section of CLOSURE #8 features three further, diverse approaches to the theory and practice of sequential art. In »Graphic Storytelling: Teaching Experience and Utility,« Darren C. Fisher explores the social affordances of drawing. He stresses its importance for developing several art forms and its potential for mental health resilience and slow-living skills. Fisher argues that drawing is a fundamental means of human expression, which varies according to age-group or cultural background. His contribution reconceptualizes drawing as »tool of enjoyment« and aims to reunite two binary approaches, namely ›observational drawing‹ and ›memory drawing.‹ In this regard, he critically observes that concepts of drawing such as Csikszentmihalyi’s ›flow theory‹ conflict with contemporary norms such as the affinity for all-encompassing productivity. These norms, as Fisher puts it, »are challenging barriers to overcome, particularly in teaching adults to draw.« The article closes with a brief description of how its theoretical premises shaped the design of an online comics workshop held as part of CLOSURE’s 2020 International Autumn School.

Barbara M. Eggert’s article is entitled »Never Judge a Book by Its Cover? Picturing the Interculturally Challenged Self in the Japanese Journals of European Comics Artists Dirk Schwieger, Inga Steinmetz, and Igort.« She proceeds from the observation that since the 1990s, Japan, as the birthplace of manga and anime, has been attracting many European comics artists who went there for inspiration and/or work. With Dirk Schwieger’s Moresukine (2006), Igort’s Quaderni giapponesi/Japanese Notebooks (2015/17), and Inga Steinmetz’s Verliebt in Japan (2017), this article analyzes and compares three heterogeneous examples concerning their comic-specific depiction of intercultural experiences in Japan. Focusing on self-representation in panels and pages that deal with phenomena such as culture shock and assimilation processes, the paper discusses if, how, and to what effect these autobiographically inspired comics – in spite or because of their varying degrees of fictionalization and comicification – echo and/or contradict some ›classical‹ intercultural adaptation theories. Eggert positions her case studies in the tradition of the travel journal, while at the same time paying close attention to their specific comics-ness – and the »medium-specific possibilities of comics to focus, exaggerate, and to leave things out.« In her detailed account of this mode of intercultural representation, Eggert lay bare the precise affordances of comics in approaching, perceiving, and misperceiving the culture of others.

In »Rhetoric of Images. Emblematic Structures and Craig Thompson’s Habibi,« Julia Ingold examines how the ›rhetoric of images‹ and the figurative nature of text in emblems and comics resemble each other. In the first part of her article, Ingold analyzes select emblems taken from Alciatio’s Emblematum liber to explore their intricate relation between text and image. More specifically, she attends to the use of metaphors, symbols, and the formation of allegorical entities in emblems. In her reading of Habibi, the author expounds the potential of the comics medium. She argues that pictorial narration can use metaphors and symbols taken from ›the reader’s world‹ without implementing them in the diegetic world of the comic. She notes that in comics, »something that is traditionally written, becomes a mimetic drawing, just as in the picturae of the emblems.« Ingold eventually identifies two strategies that apply to both emblems and comics: they highlight their own figurativeness and use images like writing in syntactic structures. Emblems and comics scrutinize the function of words and images. Thus, they allow for a new language which, as the author concludes, transforms the invisible into visible images which become rhetoric.

In addition to our articles, CLOSURE #8 features a smorgasbord of reviews, offering in-depth discussions of contemporary comics scholarship, comics, and graphic novels. In our section ›Comic Context,‹ we recap the inaugural CLOSURE Autumn School, which discussed the knowledge inscribed in and mediated by sequential art: ›What Do Comics Know?‹. The section includes a graphic recording by Tim Eckhorst, who was not only a workshop leader but also captured the discussions in inimitable style – and thereby created a nonfiction comic that encapsulates some of the ›non-narrative‹ concerns of this issue.

Kiel, November 2021

Cord-Christian Casper and Kerstin Howaldt for the CLOSURE-Team

_______________________________________________________

Bibliography

- Baetens, Jan: Abstraction in Comics. In: SubStance 40 (2011), p. 94–113.

- Bukatman, Scott: Sculpture, Stasis, the Comics, and Hellboy. In: Critical Inquiry 40 (2014), p. 104–117.

- Kukkonen, Karin : Studying Comics and Graphic Novels. Chichester, Malden, MA, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- McCloud, Scott: Understanding Comics. New York: HarperPerennial 1994.

- Molotiu, Andrei: Abstract Form. Sequential Dynamism and Iconostasis in Abstract Comics and in Steve Ditko’s Amazing Spider-Man. In: Critical Approaches to Comics. Theories and Methods. Ed. Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan. New York: Routledge 2012, p. 84–100.

- Strawson, Galen: Real Materialism and Other Essays. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008.

Herausgeber_innen

Victoria Allen

Cord-Christian Casper

Constanze Groth

Kerstin Howaldt

Julia Ingold

Gerrit Lungershausen

Dorothee Marx

Garret Scally

Susanne Schwertfeger

Simone Vrckovski

Dennis Wegner

Rosa Wohlers

Redaktion & Layout

Victoria Allen

Cord-Christian Casper

Sandro Esquivel

Constanze Groth

Kerstin Howaldt

Arne LĂĽthje

Julia Ingold

Gerrit Lungershausen

Dorothe Marx

Garret Scally

Alina Schoppe

Susanne Schwertfeger

Simone Vrckovski

Dennis Wegner

Rosa Wohlers

Technische Gestaltung

Sandro Esquivel

Marie-Luise Meier

Cover & Illustrationen

Gareth A. Hopkins (Ausgabe #8)

Kontakt

Homepage: www.closure.uni-kiel.de

E-Mail: closure[@]email.uni-kiel.de