›Constructions and Subversions of the Body in Comics‹ – About this Issue

Irmela Marei KrĂĽger-FĂĽrhoff (Berlin), Nina Schmidt (Berlin)

The variety of auto(biographical), documentary and fictional comics, some of which have won prestigious awards, proves that there is basically nothing that cannot (also) be depicted or imagined in comics. Accordingly, the field encompasses: humorous strips; reflections on genocide and refugee experiences; adolescents’ search for identity and the exploration of family secrets and sexuality; the critical depiction of geopolitical conflicts; the design of fantastic worlds; and ›realistic‹ confrontations with the nadirs of the quotidian. What almost all comics have in common is that they depict their protagonists in specific bodies: we encounter drawn or painted, and thus constructed bodies, even if they emphasize their ›madeness‹ to varying degrees. Elisabeth El Refaie (8), a literary and communication scholar, informs us that these bodies possess a »pictorial embodiment« including facial expressions, gestures, and movements, which form the basis (and sometimes the limit) of their agency in the storyworld. US-American comic theorist Will Eisner (103) goes so far as to assign greater agency to body representation in the image-text medium of comics than to language; he declares: »In comics, body posture and gesture occupy a position of primacy over text.«

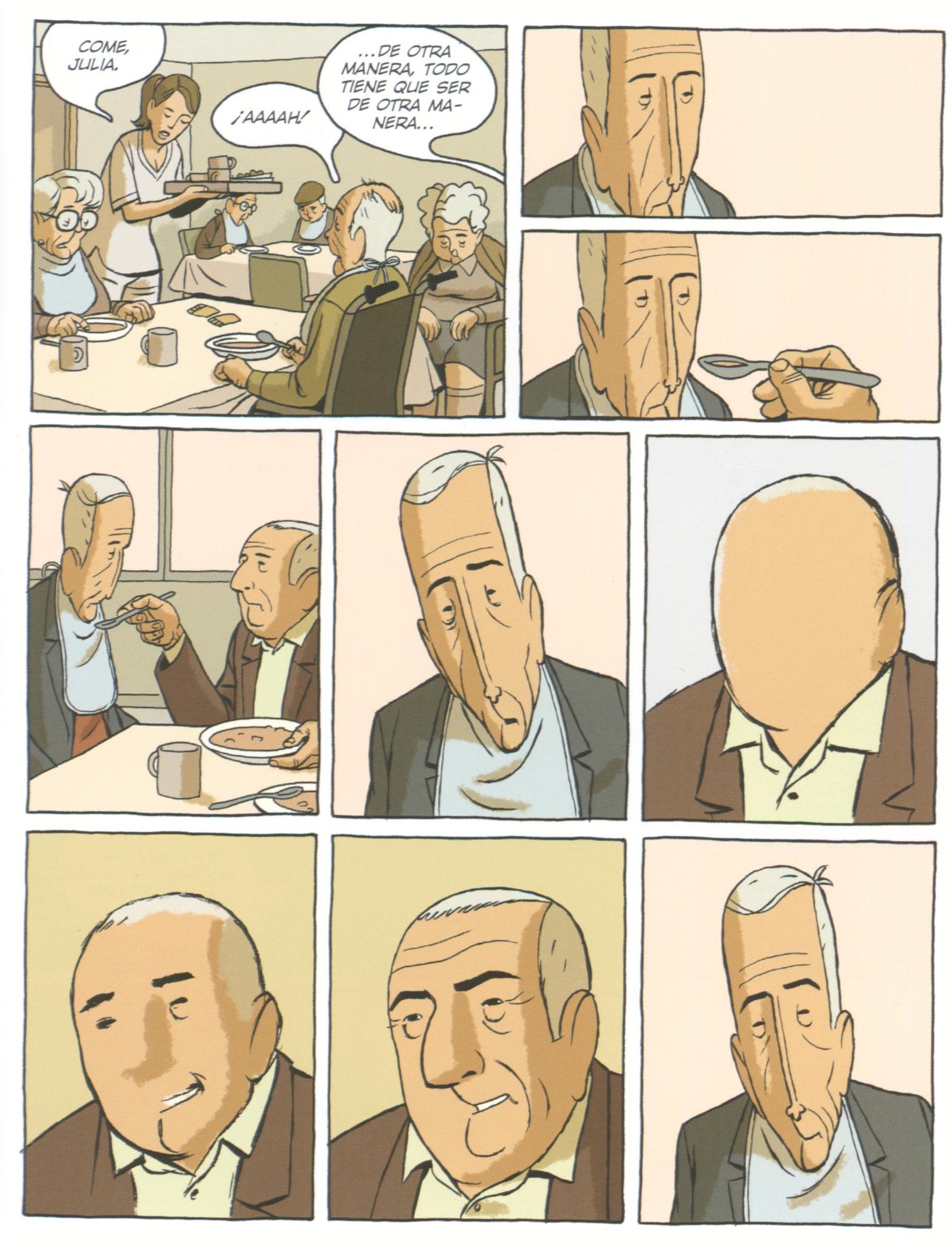

Embodiments in comics are not only reflected in activities recognizable from the outside, but they also convey feelings and inner processes; according to artist MK Czerwiec and American studies scholar Michelle N. Huang, comics »are uniquely suited to representing embodied experience« (Czerwiec/Huang, 97). This embodiment of experience includes feelings such as fear, pleasure, doubt, sadness, or anger; it affects the protagonists’ self-representations and, ultimately, their interactions with their environment. Paco Roca’s comic Arrugas from 2007 is a case in point illustrating how inner experiences are represented through the body on the page. Arrugas centers on Emilio, who lives in a retirement home and whose perception of the world and ability to act meaningfully within it are increasingly affected by dementia. In one of the final scenes (fig. 1), Emilio is fed by his roommate and friend Miguel. Using internal focalization, the comic depicts Miguel from Emilio’s perspective and shows Miguel’s face as an outline, a mere surface or geometric shape; the emptying face of his counterpart illustrates, indeed embodies, Emilio’s increasing disorientation (cf. Fraser, 165-166; Hertrampf, 18-19).

It is only the sequence of images and the connection with the collar and shoulders that help readers identify the round shape in the last panel as a human head. We understand that Emilio’s inability to recognize his friend’s face and, thus, ›read‹ his feelings, expresses Emilio’s loss of memory; his dementia is thus conveyed through the representation of an ›alien‹ body (no longer familiar to him) and entirely without words. Ultimately, the ›loss‹ of Miguel’s body, visualized through simplification and omission, represents the impending dissolution of Emilio’s own sense of self, and it seems logical that Emilio’s inner experience (or our interpretation of that experience) results in a page that remains one-third white.

Because comics – unlike literary texts and more like films – can and must visualize their protagonists, they give them a shape that we understand to be a body, no matter how alien, grotesquely overdrawn or – as in the example from Arrugas – reduced it may be. Comics can present bodies as unchangeable (in most comic book series, characters hardly age)1, or, on the contrary, as infinitely changeable and even immortal (when characters are resurrected slapstick-like after each and every misfortune, for example); comics endow bodies with comprehensive agency (see: superheroes) or reflect their limitations; they present de-sexualized or highly sexualized bodies; in visualizations of mutants, chimeras, and zombies they play with cultural boundaries between wholeness and dissolution, naturalness and artificiality, death and life; they design individual bodies and often also collective bodies. Regardless of whether all of this is stereotyping, caricature, or wishful thinking, comics convey cultural notions of human, animal, anthropomorphic, or technological bodies; of masculinity, femininity, or queerness; of age, ethnicity, and cultural context; of social class and physical or mental ability. And of course, these aspects usually do not exist in isolation, but appear in complementary or conflicting constellations, thus forming intersectional ensembles (cf. Eckhoff-Heindl/Sina). The choice of specific visualizations in comics can make the sociocultural contexts of these embodiments apparent and for this reason it becomes »a profoundly social and political activity« (El Refaie, 73). Comics thus give us bodies to see, expecting our reactions, which are shaped by societal expectations and individual experiences.2 In this, comics are neither affirmative nor subversive, per se, but they can be understood as seismographs of and (possibly critical) commentaries on cultural normalizations, hopes, fears, and sociopolitical developments. It is precisely this perspective that underlies the articles collected in the present issue.

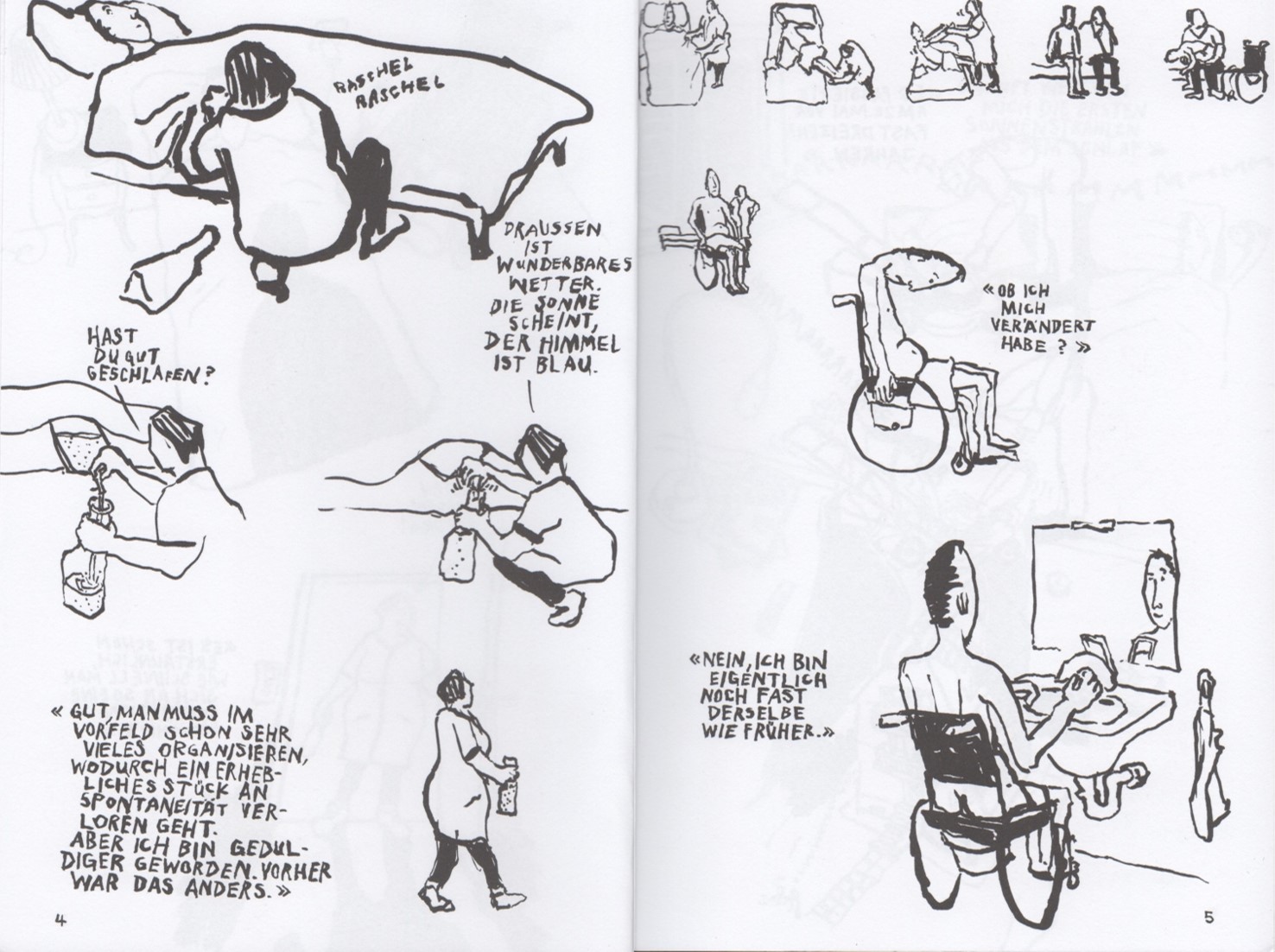

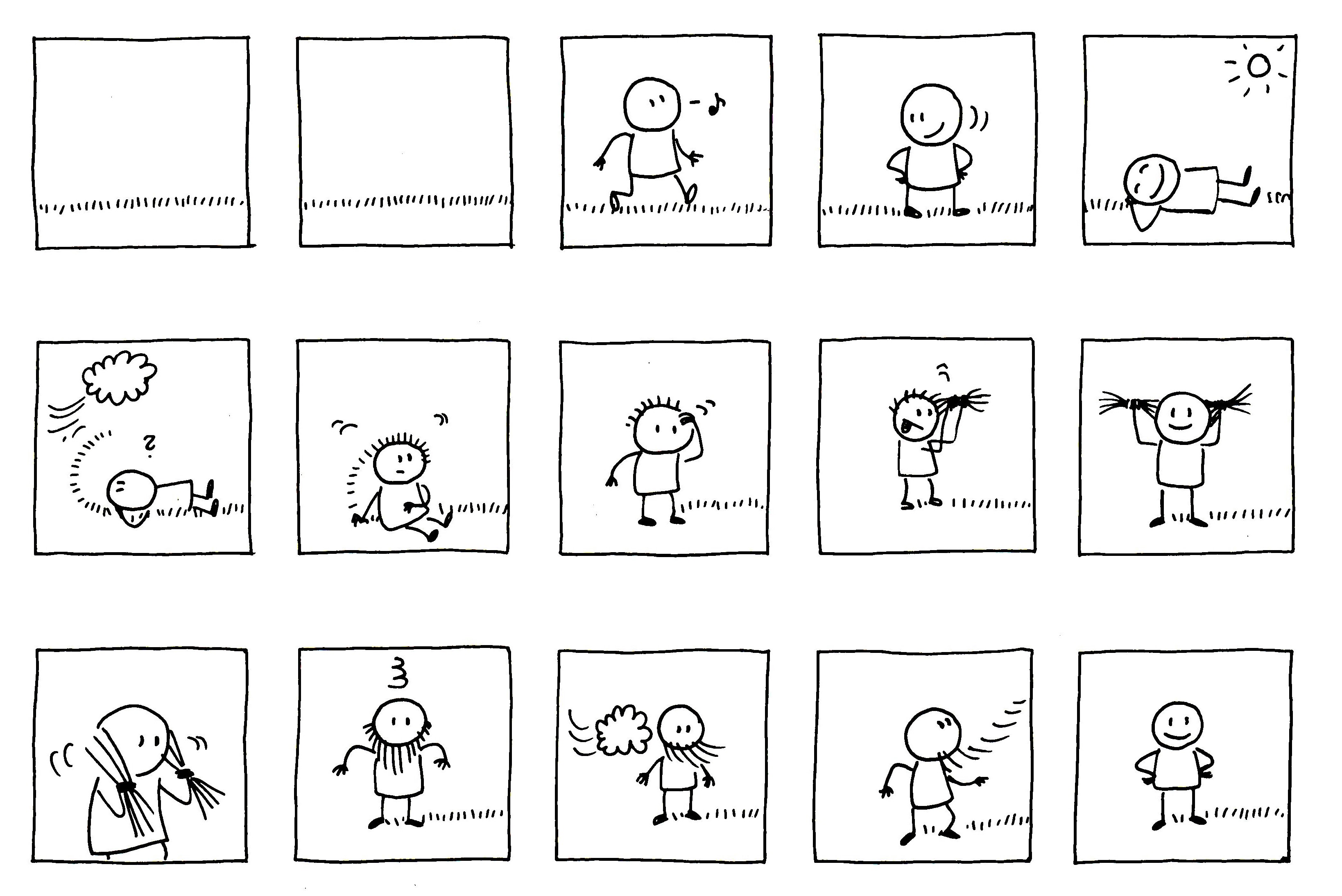

Recent comics research, which adopts approaches from media theory, cultural studies, gender and diversity studies, and disability studies, has pointed out that bodies are continually produced anew in the varying repetition of individual comic panels. In this way, bodies are not only ›confirmed‹, but rather – in the sense of Judith Butler’s theories of performativity – their constructedness and changeability (cf. Klar) and often also their vulnerability become foregrounded (cf. Engelmann, 109-194). Thus, literary scholar Elisabeth Klar (232) emphasizes: »Every panel not only means a threat to continuity, but also an opportunity for change.« In the same vein, the German studies and comics scholar Anna Beckmann (92) attests to comic’s specific »aesthetics of repetition and rupture,« which makes this medium particularly capable of »revealing ambivalences, indeterminacies, and gaps in meaning.« This mediality also makes the comic a promising medium for reflecting on questions of body and gender theory. Admittedly, this is not always as light-hearted and cheerful as on the opening page from the comic strip Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst (2010; »I spy (with my little eye)«) by Imke Schmidt and Ka Schmitz, which features a stylized and extremely flexible human figure (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Small strokes, big impact: reflections on questions of body and gender theory in Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst.

Fig. 3: »Do you feel represented now?« Hidden pictures are (not) a solution in Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst.

With ›disability‹ and ›trauma‹ we would next like to focus on two topics that show how comics pay special attention to the corporeality of their protagonists. There are bodies that stand out in public space – the bodies of people with a visible disability, for example. In general (discriminatory) perception, they are either ›lacking‹ something – symmetry, for example, or the sense of hearing or sight – or they are characterized by ›excess‹ – erratic gestures, for example, or aids that are deemed too conspicuous. In art and culture, on the other hand, those living with illness or disability often notice the absence of bodies (and, consequently, realities of life) that resemble their own. In comics, and more precisely in the field of graphic medicine, more and more different bodies are now finding a place, including those with illnesses and disabilities (see, among others, Czerwiec et al.; Foss et al.; Wegner).3

The medium of comics thus tackles the lack of visibility of dis/abled communities, becomes a space for the narration of dis/abled lives, and does not ›only‹ address those readers who identify as disabled themselves. Even if German-language comics cannot be considered pioneering here, two German-language examples may illustrate how disability (as a deviation from a socially imagined norm of integrity and ablebodiedness) is portrayed and what questions this raises with regard to corporeality, perception of self and others, and mechanisms of belonging or exclusion.

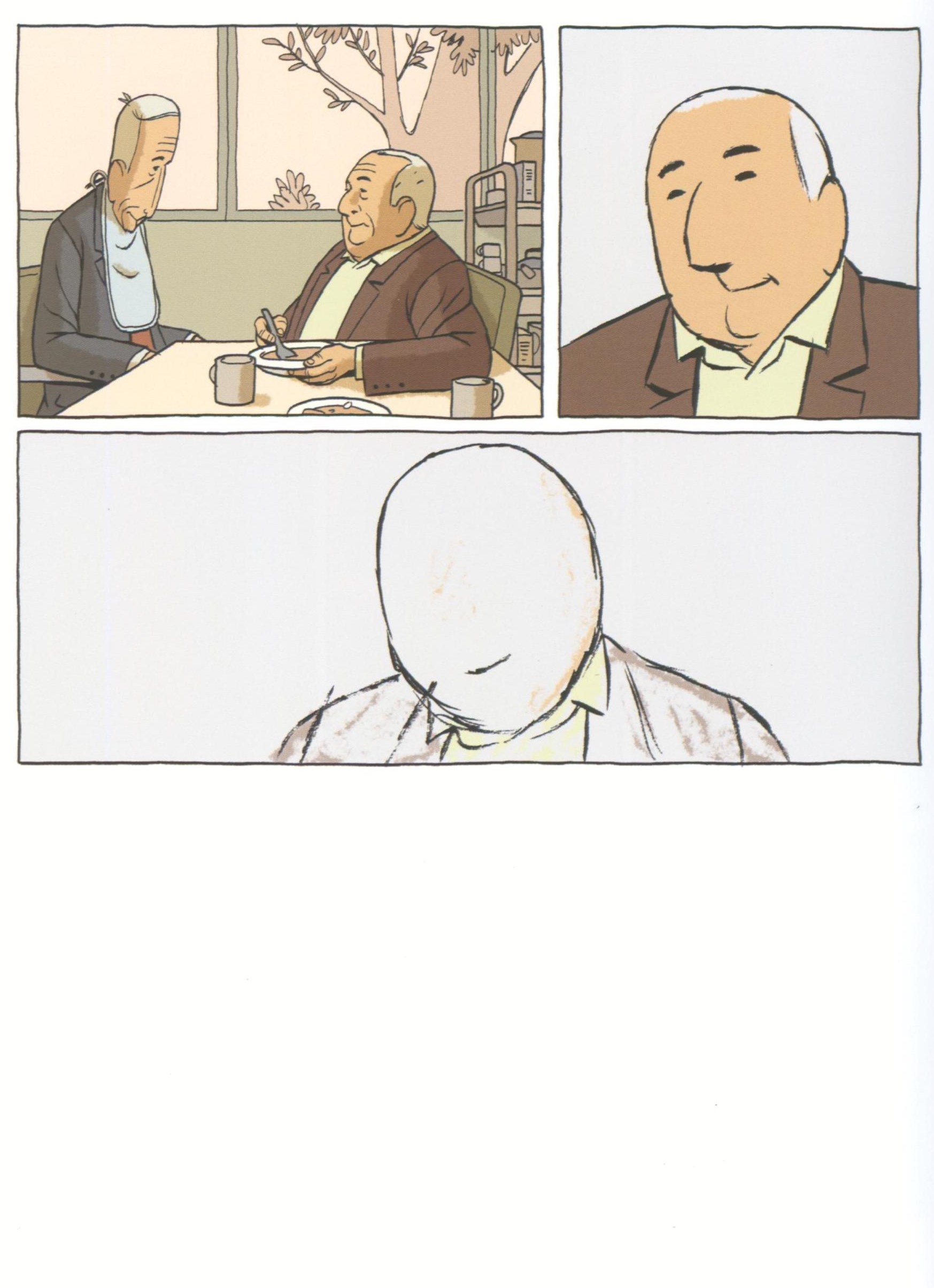

The first three pages of Roland Burkart’s comic Wirbelsturm (2017, Whirlwind) introduce us to the everyday routine of Piedro, who has become quadriplegic due to a swimming accident thirteen years earlier. He is the object of a professional nurse’s caring activities (fig. 4). His body is very much in the foreground in this opening scene (and, indeed, throughout the book) – readers literally get pictures of the many steps necessary in the daily care routine. Although the accident has visibly changed Piedro’s physicality, he puts it into perspective: »I am actually almost the same as before« (Burkart, 5). This may surprise some nondisabled readers, as they may expect a more drastic distinction between life before and after the accident, and for them, the protagonist’s statement may not fit the representations of his body in the comic. But this is precisely why it is important: a tension is created between image and text that can only be resolved if we understand that Piedro is speaking of himself as a personality; the body is only part of the whole.

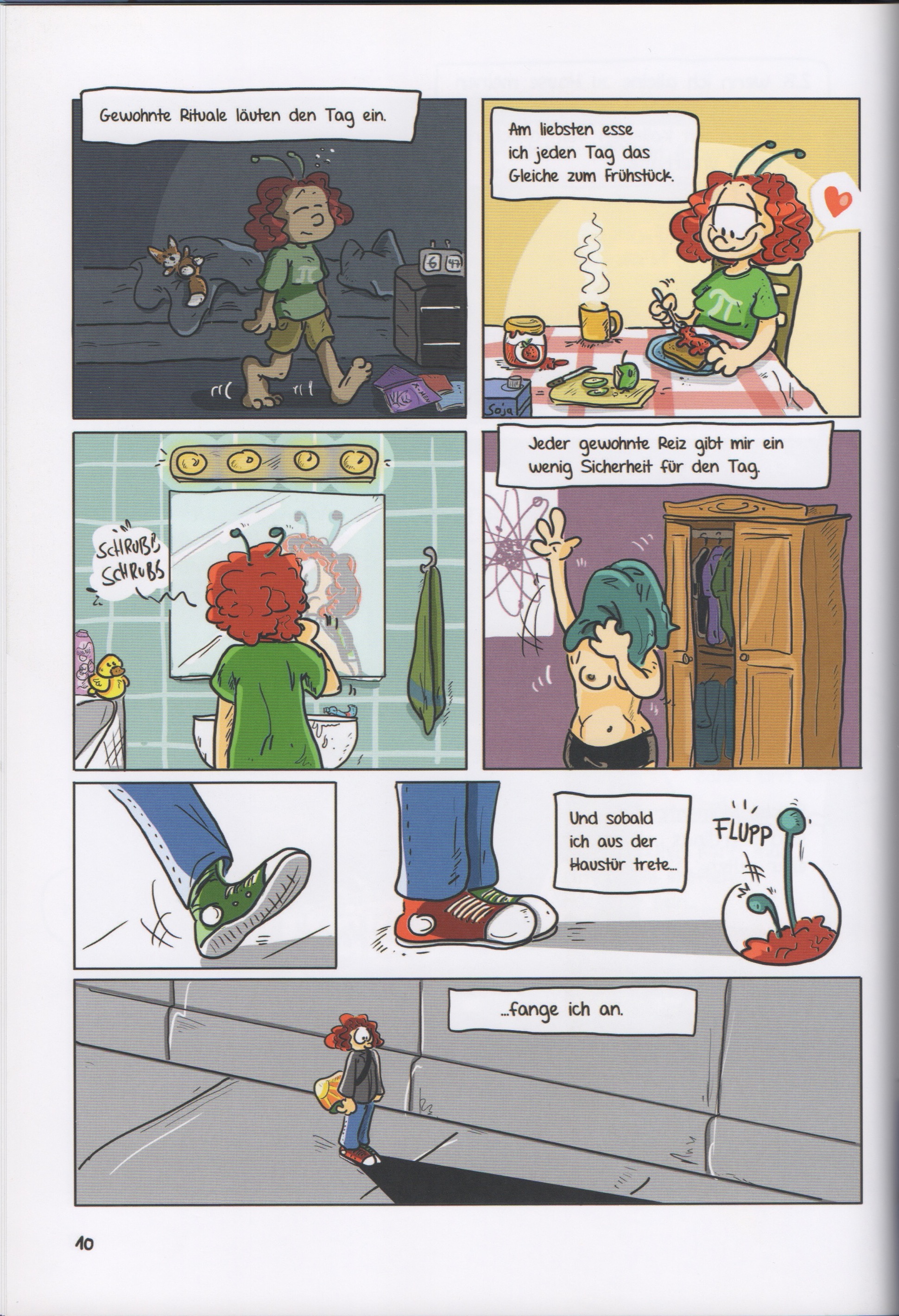

The next example pursues a contrary strategy, in a sense, because here, a disability that is not actually visible (and not always severe) is explicitly visualized on the comic body. The comics artist Daniela Schreiter is known for her Schattenspringer trilogy (2014-2018). In the trilogy, she treats the subject of Asperger’s (an autism spectrum disorder) autobiographically. The first volume is primarily about her childhood and the long road to diagnosis. Compared to Wirbelsturm, Schattenspringer deals with a physical difference that is more subtle but is nevertheless (or precisely because of its lack of visibility) shown through the body of the alter ego character in the comic (fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Visualizing th self-image on the comic-body:

Daniela Schreiter’s ›antennae‹ in Schattenspringer.

Schreiter gives her avatar antennae or feelers because her form of autism is also nicknamed ›wrong planet syndrome‹; she adopts the linguistic image because it approximates her experience of the world and everyday life as alien (cf. Schreiter, 8; Göhlsdorf, 291). With her antennae, Schreiter marks herself as ›different‹ in the sense of being ›exceptional‹ – she thus presents herself as more sensitive than neurotypical people. Her perception of touch and other senses is both more uncontrolled and more intense, which is why fellow humans often cannot comprehend her reactions to her environment. Accordingly, drawing herself as being equipped with antennae is not a visualization of a stigma, but a gesture of self-empowerment, insisting that the ›other‹ experience is neither imaginary nor necessarily a deficit. This is also important in regard to the history of medical research on autism, which is characterized by misconceptions (autism as a form of schizophrenia), negative images, or even blame, assigned to the parents of affected children, for example (cf. Göhlsdorf, 280–285; ¬Kumbier et al., 55–60). The character’s antennae are extended when she is relaxed and able to fully be herself (cf. Alegiani, 35); this is predominantly the case in her own home, for instance directly after getting up. Like Wirbelsturm, Schattenspringer addresses morning routines during the opening of the comic. On the whole, this page from Schattenspringer emphasizes the difference between indoors and outdoors, the comfortable home and the outside environment. ›Out there‹ the character grows smaller (last panel), the challenges that await her become all the greater, and yet the words put in her mouth are in the active voice: »as soon as I step out the front door.... / ...I start.« The comic-body transforms, thus reflecting externally what is happening internally, namely that the character consciously begins to behave as neurotypically as possible. In this way, the autistic person’s active doing is emphasized, as somebody who approaches her fellow human beings, shows them understanding, so to speak, and adapts to them, because, unfortunately, she can only expect this to a limited extent the other way around. Even if Schreiter’s depiction cannot and does not want to stand for the experience of all autistic people (cf. Schreiter, [7], 157), comics like Schattenspringer generate rare moments of recognition for a part of their readership and thereby create community and identity, to a certain degree.

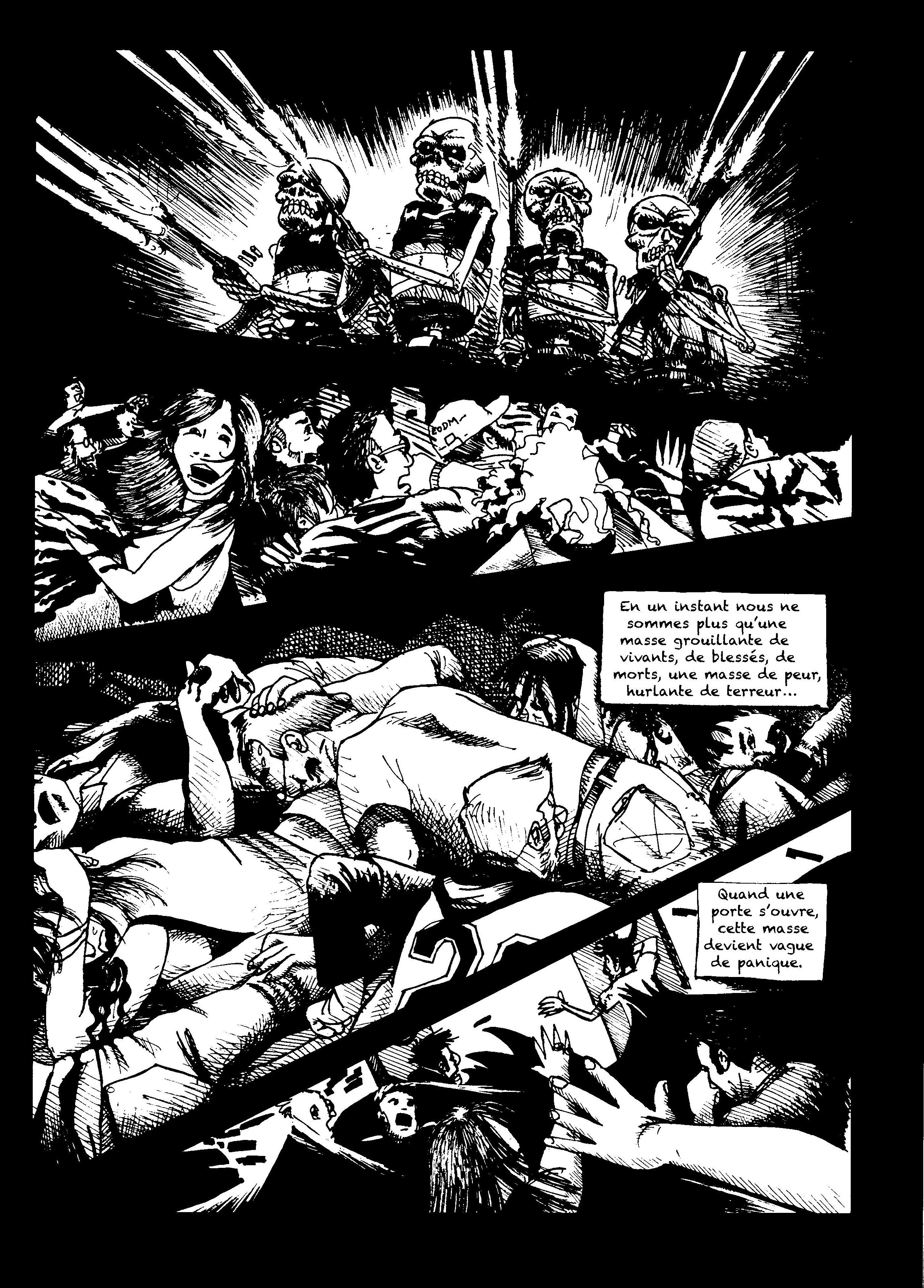

Just as shared corporal experience can create community, a representation of different bodies as resembling each other can point to potential similarities. This is precisely what is avoided in some comics that share stories of violence and trauma and in doing so focus on the victims’ perspective. These comics not only want to convey the experience of violence and the concomitant break between the normality of a ›before‹ and the instability and woundedness of an ›after‹, but also to create distance between themselves and the perpetrators on a visual level, as the latter have brutally crossed physical and psychological boundaries. This targeted othering of the perpetrators by the victims of violence and trauma, indeed, the occasional retrospective dehumanization of the perpetrators, also occurs through bodily representations. At the same time, the comics may be concerned with avoiding a voyeuristic view of the victims. The two visual strategies of distancing oneself from the body of the perpetrators and of protecting the victims are evident in two autobiographical French comics that deal with the Islamist attack on the editorial office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015, and the terrorist attack in the Bataclan neighborhood of Paris on November 13 of the same year.

Published in 2016, Mon Bataclan by graphic artist and medical illustrator Fred Dewilde combines comic book pages with written reflections on life after and with trauma. One of the pages about the terrorist attack (fig. 6) is divided into four differently tapered panels and conveys two opposing messages through the depictions of bodies: on the one hand, the assassins are clearly recognizable as such as they are positioned victoriously above the fleeing or prostrate »masse grouillante« of concertgoers,4 some of whose fragmented body parts can no longer even be clearly assigned. On the other hand, Dewilde denies the perpetrators any individuality. As skeletons reminiscent of the four apocalyptic horsemen of the biblical Book of Revelation (or their pictorial realization by Albrecht Dürer, among others), they are not only messengers of death, but already lifeless figures themselves, whose lack of humanity is denoted in their empty stares and clenched teeth, while the wide open eyes and mouths of the desperate victims appeal to our pity and endow them human individuality.

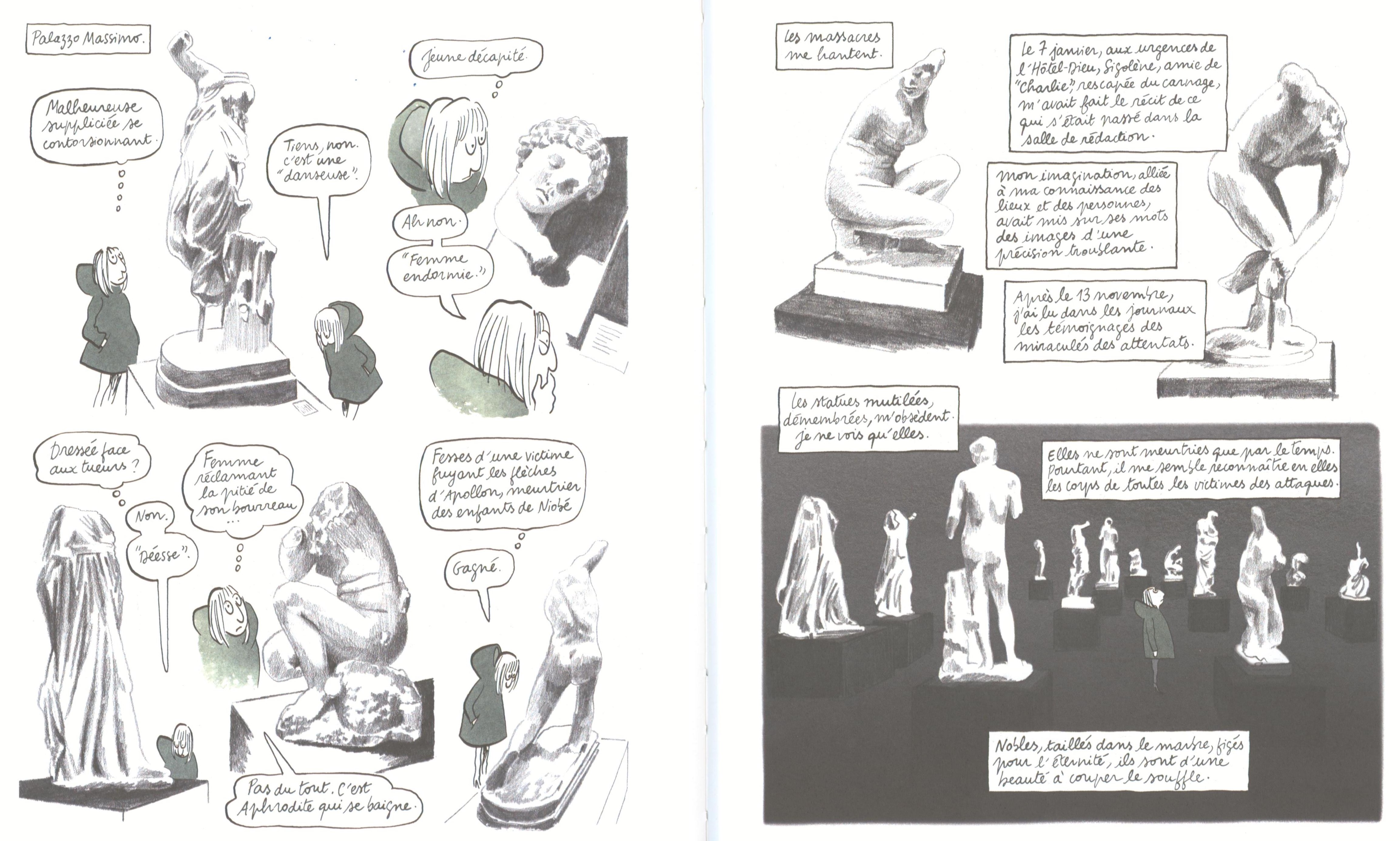

The medium of comics has repeatedly been said to be particularly well suited to convey existentially threatening experiences. Media-specific reasons for this are, for example, the tension between image and text, between single image and panel sequence, between simultaneous and successive perception, all of which can aptly convey threats to existence, such as life-threatening illnesses (cf. Waples; Williams) or continuity-shattering experiences of traumatization (cf. Chute 2010, 2016; Davies/Rifkind). In this sense, the alienation, de- and recontextualization of bodies in comics can contribute to self-empowering reflections about trauma. The autobiographical comic La légèreté (2016) by Catherine Meurisse illustrates that the imaginary confrontation between ›real-flesh‹ and artificial bodies of artistic creation may be used for this purpose. The cartoonist and Charlie Hebdo contributor escaped the attack on the satirical magazine by chance, arriving late for work. However, she lost most of her colleagues and friends and was under personal protection for a long time due to the threat of further attacks. In her internationally acclaimed comic, which depicts her difficult return to some degree of normality, Meurisse draws on numerous examples from literature, painting, architecture, and sculpture to describe the importance of art in gradually overcoming her trauma. The artist did not see the corpses of her dead colleagues and does not show them in her comic. Instead, she takes a detour by looking at antique statues, whose decay and lost limbs remind her of those massacred in Paris (fig. 7). Meurisse’s first-person protagonist declares:

Les statues mutilées, démembrées, m’obsèdent. [...] / Elles ne sont meurtries que par le temps. Pourtant, il me semble reconnaître en elles les corps de toutes les victimes des attaques / Nobles, taillés dans le marbre, figés pur l’éternité, ils sont d’une beauté à couper le souffle. (Meurisse 2016, 111)5

The construction of ideal corporeality in ancient sculpture shapes our understanding of beauty to this day; depending on the historical situation, their damage or ›mutilation‹ was overlooked in past centuries, overcome by the power of thought or handiwork, or contemplated as memento mori (cf. Krüger-Fürhoff). Meurisse draws a parallel between the auratic marble bodies exhibited in museums with the bodies of the twelve members of the editorial staff shot dead, and while not giving them individual faces at this point in the comic, she does give them ›representative‹ bodies that are considered damaged and yet beautiful. In this way, La légèreté restores the terror victims’ dignity and memorializes them, thus promising them a place in collective memory.

This thematic issue goes back to the lecture series Comic – Kunst – Körper. Konstruktion und Subversion von Körperbildern im Comic, which took place in the winter semester 2020/21 at Freie Universität Berlin. The event arose from the ›PathoGraphics‹ research project on illness narratives in literature and comics, funded by the Einstein Foundation Berlin; financial and organizational support came from the executive board (Präsidium) of the Freie Universität Berlin, the staff of the program Offener Hörsaal, and the Women’s Representative of the Department of Philosophy and Humanities. The thirteen lectures by colleagues as well as artists from Berlin and other German universities, Argentina, Austria, Poland, and the United States were made available via videoconferencing software and a livestream due to Coronavirus restrictions. We are proud to say they attracted a broad international audience of students, colleagues, and interested parties from diverse fields. And we would like to thank all participants of the lecture series – it was a great event that was fun and inspiring to us.

We are pleased to be able to present a revised version of more than half of the contributions to the lecture series in this issue and would like to thank Dorothee Marx and Susanne Schwertfeger for the enthusiasm with which they welcomed us as guest editors of CLOSURE. The cover is by stef lenk, whose permission to publish the artwork we are glad to have.

Véronique Sina’s essay Comic, Körper und die Kategorie Gender: Geschlechtlich codierte Visualisierungsmechanismen im Superheld_innen-Genre (Comics, Bodies, and the Category of Gender: Gender Coded Visualization Mechanisms in the Superhero Genre) opens the issue. It starts from two premises: first, that to draw and overdraw bodies in comics is practically -inevitable, and second, that bodies in comics are always gendered bodies. Sina’s critical analysis of the good and bad girls of the superhero genre makes clear that comics possess subversive potential, but do not always bring it to fruition; thus, the medium in itself is not yet a guarantee for progressive content.

Following this is Daniel Stein’s English-language contribution Black Bodies Swinging: Superheroes and the Shadow Archive of Lynching. Stein questions the body concepts of the US-American superhero genre by analyzing the remediation of archival lynching imagery in Jeremy Loves’ Bayou (2009; 2010) and Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner (2008). The confrontation with the representation of African American bodies in these comics both challenges and enables an examination of the genre’s racist visual archive as well as the history of the United States as a whole.

In Körper/Blicke und Selbst(be)zeichnungen bei Pagu, Laerte und Powerpaola (Bodies/Gazes and Self-designation in Pagu, Laerte and Powerpaola), Jasmin Wrobel examines South American sequential art as an artistic space of resistance and a place of negotiation for feminist discourses. Analyzing comics by ›Pagu‹, Laerte Coutinho and Paola Gaviria aka ›Powerpaola‹, Wrobel looks at militant, queer/non-binary and anti-patriarchal bodies whose activities combine autobiographical with political perspectives.

Kalina Kupczyńska’s essay (Frauen)Körper und gleichgeschlechtliches Begehren als Politikum im polnischen Alternativen Comic ((Women’s) Bodies and Same-Sex Desire as a Point of Political Contention in Polish Alternative Comics) examines comics that oppose mainstream aesthetics as well as conservative modes of thought and behavior. They recall repressed chapters of Polish history, retell identity-forming narratives, and create non-heteronormative characters that do not officially exist in Polish society. In doing so, Kupczyńska’s analyses illustrate how the alternative Polish comics scene critically questions established cultural connections between body, gender, and nation.

In Die Breitbeinigen: Aufklärungsmodi und Körperpolitiken in deutschsprachigen feministischen Comics (Legs Apart: Modes of Enlightenment and Body Politics in German-Language Feminist Comics), Nina Schmidt argues that the feminist-activist comic of today enlightens/educates in two ways at once: with view to history (or rather, herstory) and in relation to the human body (especially the body constructed as female). She shows how contemporary comics engage in body politics and examines why the image-text medium is particularly suited to addressing political aspects of corporeality.

Under the title Ebenbilder und Fremdkörper: Figurenmultiplikationen im Werk von Patrice Killoffer (Likenesses and Foreign Bodies: Figure Multiplications in the Work of Patrice -Killoffer), Marie Schröer asks what the media-specific characteristic of comics (re)producing the image of a body in (almost) every panel means for notions of individuality, authenticity, originality and imitation – and for concepts of masculinity. In doing so, she bridges the gap between the body in comics and the comic book as a corporeal object and shows how Patrice Killoffer’s works (self-)ironically inscribe themselves in current literary and philosophical discourses.

The thematic issue concludes with Irmela Marei Krüger-Fürhoff’s essay Entfaltungen: Alternde Körper im Comic (Unfoldings: Aging Bodies in Comics), which uses examples from different countries and languages to analyze how comics contribute to the diversification of cultural narratives and media images of age and aging through the physical design of their protagonists. In aesthetically diverse ways, the drawn and narrated characters break stereotypes and wrestle with physical relationships, individual agency, and (sociopolitical) participation.

We hope that the seven contributions to this special issue will fuel further investigations of the body in comics.

Berlin, July 2021

Irmela Marei KrĂĽger-FĂĽrhoff und Nina Schmidt

_______________________________________________________

Bibliography

- Alegiani, Assunta: Drawing Out the Invisible Difference. Autism-Spectrum-Disorder in Educational and Auto/biographical Comics. Unpublished MA thesis, Freie Universität Berlin, 2020.

- Beckmann, Anna: »Glaub mir nicht, ich bin ein Comic«. Selbstreflexivität im Comic als Markierung narrativer Unzuverlässigkeit. In: Closure. Kieler e-Journal für Comicforschung 4.5 (2018), p. 92–105. <http://www.closure.uni-kiel.de/closure4.5/beckmann>. 10.05.2018. Accessed 15.03.2021.

- Burkart, Roland: Wirbelsturm. ZĂĽrich: Edition Moderne, 2017.

- Chute, Hillary: Disaster Drawn. Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Chute, Hillary: Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

- Czerwiec, MK et al. (ed.). Graphic Medicine Manifesto. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2015.

- Czerwiec, MK and Michelle N. Huang: Hospice Comics: Representations of Patient and Family Experience of Illness and Death in Graphic Novels. In: Journal of Medical Humanities 38 (2017), p. 95–113.

- Davies, Dominic and Candida Rifkind: Documenting Trauma in Comics. Traumatic Pasts, Embodied Histories, and Graphic Reportage. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020.

- DeTora, Lisa and Jodi Cressman: Graphic Embodiments. Perspectives on Health and Embodiment in Graphic Narratives. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021.

- Dewilde, Fred: Bataclan. Wie ich ĂĽberlebte. Transl. by Bettina Frank. Stuttgart: Panini, 2017.

- Dewilde, Fred: Mon Bataclan. Paris: Lemieux, 2016.

- Eckhoff-Heindl, Nina and VĂ©ronique Sina (eds.): Spaces Between. Gender, Diversity, and Identity in Comics. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020.

- Eisner, Will: Comics and Sequential Art. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press, 1985.

- El Refaie, Elisabeth: Autobiographical Comics. Life Writing in Pictures. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2012.

- Engelmann, Jonas: Gerahmter Diskurs. Gesellschaftsbilder im Independent-Comic. Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2013.

- Foss, Chris, Jonathan W. Gray and Zach Whalen (Hg.): Disability in Comic Books and Graphic Narratives. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Fraser, Benjamin: Cognitive Disability Aesthetics. Visual Culture, Disability Representations, and the (In)Visibility of Cognitive Difference. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

- Gohlsdorf, Novina: Autismus. Diagnose der Gegenwart. In: Kinder- und Jugendlichen-Psychotherapie: Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse und Tiefenpsychologie 182.2 (2019), p. 277–303.

- Hertrampf, Marina Ortrud M.: Die Visualisierung des Nichtsagbaren oder das Verschwinden der Bilder in Paco Rocas Arrugas (2007). In: Medienobservationen. 26.03.2012. <www.medienobservationen. lmu.de>. Accessed 15.03.2021.

- Klar, Elisabeth: Wir sind alle Superhelden! Über die Eigenart des Körpers im Comic – und über die Lust an ihm. In: Theorien des Comics. Ein Reader. Eds. Barbara Eder, Elisabeth Klar and Ramon Reichert. Bielefeld: transcript, 2011, p. 219–236.

- Krüger-Fürhoff, Irmela Marei: Der versehrte Körper. Revisionen des klassizistischen Schönheitsideals. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2001.

- Kumbier, E., Domes, G., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. et al.: Autismus und autistische Störungen. In: Nervenarzt 81 (2010), p. 55–65.

- Meurisse, Catherine: Die Leichtigkeit. Transl. by Ulrich Pröfrock. Hamburg: Carlsen, 2017.

- Meurisse, Catherine: La légèreté. Paris: Dargaud, 2016.

- Quesenberry, Krista: Intersectional and Non-Human Self-Representation in Women’s Autobiographical Comics. In: Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 8.5 (2017), p. 417–432.

- Roca, Paco: Arrugas. Bilbao: Astiberri, 2013 [2007].

- Roca, Paco: Kopf in den Wolken. Transl. by André Höchemer. Berlin: Reprodukt, 2013.

- Schmidt, Imke (W/P) and Ka Schmitz (W/P): Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst. LIGHTfaden fĂĽr BILDERmacher_innen. Berlin: GenderKompetenzZentrum, 2010.

- Schreiter, Daniela: Schattenspringer. Wie es ist, anders zu sein. Stuttgart: Panini, 2014.

- Squier, Susan Merrill and Irmela Marei KrĂĽger-FĂĽrhoff (Hg.): PathoGraphics. Narrative, Aesthetics, Contention, Community. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2020.

- Szep, Eszter: Comics and the Body. Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2020.

- Vollbrecht, Ralf: Der Körper im Comic. In: Körpergeschichten. Körper als Fluchtpunkte medialer Biografisierungspraxen. Eds. Anja Hartung-Griemberg, Ralf Vollbrecht and Christine Dallmann: Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2018, p. 237–250.

- Waples, Emily: Avatars, Illness, and Authority: Embodied Experience in Breast Cancer Autopathographics. In: Configurations 22.2 (2014), p. 153–181.

- Wegner, Gesine: Reflections on the Boom of Graphic Pathography. The Effects and Affects of Narrating Disability and Illness in Comics. In: Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 14.1 (2020), p. 57–74.

Williams, Ian C. M.: Graphic Medicine. The Portrayal of Illness in Underground and Autobiographical Comics. Case Study. In: Medicine, Health and the Arts. Eds. Victoria Bates, Alan Bleakley and Sam Goodman. London/New York: Routledge (2014), p. 64–84.

List of Figures

- Fig. 1: Roca, Paco: Arrugas. Bilbao: Astiberri, 2013 [2007], p. 95–96.

- Fig. 2: Schmidt, Imke (W/P) und Ka Schmitz (W/P): Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst. LIGHTfaden fĂĽr BILDERmacher_innen. Berlin: GenderKompetenzZentrum, 2010, p. 5.

- Fig. 3: Schmidt, Imke (W/P) und Ka Schmitz (W/P): Ich sehe was, was du nicht siehst. LIGHTfaden fĂĽr BILDERmacher_innen. Berlin: GenderKompetenzZentrum, 2010, p. 9.

- Fig. 4: Burkart, Roland: Wirbelsturm. Zürich: Edition Moderne, 2017, p. 4–5.

- Fig. 5: Schreiter, Daniela. Schattenspringer. Wie es ist, anders zu sein. Stuttgart: Panini, 2014, p. 10.

- Fig. 6: Dewilde, Fred: Mon Bataclan. Paris: Lemieux, 2016, p. 11.

- Fig. 7: Meurisse, Catherine: La légèreté. Paris: Dargaud, 2016, p. 110–111.

- 1] On the »invariance of the body« and the associated recognition value, see Vollbrecht, 238.

-

2] For the physical interaction between the production and reception of comics, see Szép.

3] Research that emphasizes references to literature or to critical medical humanities also uses terms such as PathoGraphics (cf. Squier/Krüger-Fürhoff) instead of graphic medicine or speaks – in a more general way – of graphic embodiment (cf. DeTora/Cressman).

4] In the English translation, »a teeming mass of the living, the injured, and the dead« (Dewilde 2017, 9).

5] »I can’t get the mutilated statues, robbed of their limbs, out of my mind. [...] / They are only marked by time. Yet I think I recognize in them the bodies of all the victims of the attacks. / Dignified, hewn from marble, forever immobile, they are of breathtaking beauty.« (Meurisse 2017, 111).