Comics and Archives: A Handy and Helpful Guide

Comics & Archive reviewed by Lynn L. Wolff

This is one powerful little pocketbook, packed with details on the historical, theoretical, practical, and praxeological dimensions of comics and archiving comics. Anyone venturing to Germany, Japan, or North America to research comics and manga will want to take this handy guide along.

Conference publications are often heterogenous, and one is rarely enticed to read them from cover to cover. That is not the case with this slim and satisfying volume. In part this is due to the handy size and compact format as well as the concise, mostly jargon-free language of each chapter, but it is more so due to the clear focus of the volume, the manageable number of contributions, each with its own clear aims, and the intriguing ways the chapters interconnect. Anyone venturing to Germany, Japan, or North America to research comics and manga will want to take along this volume as a useful guide.

In their brief introduction to the volume, Felix Giesa and Anna Stemmann outline in broad strokes the field of comics archives and collections, drawing various points of connection between comics and archives, such as how the process of archiving always brings with it issues of canonization (9). In addition to the editors, the five contributors include scholars and practitioners with areas of expertise in popular culture and media studies as well as children’s and young adult literature. With one exception, all are affiliated with institutions in Germany, and their geographical expertise covers North America, Germany, and Japan. Within these disciplinary and geographical parameters, the volume does an excellent job – however, it would have made sense to include more details on Franco-Belgian archives and collections – and it is a positive step in the direction of discussing comics in more culturally comparative terms, rather than focusing on American or European comics separately, which is often the case in scholarly studies.

The first chapter by Daniel Stein contains valuable breadth and depth on aspects of comics history, archival practices, and popular culture. The opening pages provide a resume of core archival ideas – both theoretical and practical – that are then connected to comics as object and medium. In this way, the considerations of comics and archives laid out here serve as both foundation and touchstone for the chapters that follow. Stein’s contribution, which is the longest to the volume, could actually be two separate essays. In the first half, he provides a detailed and valuable chronological sketch of the relation between comic archives and comics studies from the 1930s up to the present day. The second part of the chapter moves away from archives and archival practices, to consider aesthetic, narratological, and media-specific aspects of comics and the archival impulse in comics, in particular to read superhero comics as a »mobile archive« (36f.)

While focusing on examples from the US, Stein differentiates between private collectors and institutional collections, but underlines the important way both work together, often made possible through the pioneering work of individual librarians, e.g., Randall Scott and Lucy Shelton Caswell in building up the Comic Art Collection of Michigan State University and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at the Ohio State University respectively (27-28). Since librarians and libraries play an important role throughout the examples in this volume, it is worth highlighting a statement by Randall Scott, which Stein quotes: »›The library profession is in a unique position to contribute to the future of scholarship by preserving 20th century popular communication artifacts, and making roadmaps through them.‹« (36) The subsequent contributions to the volume reinforce Scott’s sentiment in different ways: not only are the collections themselves important, but the narratives and arguments that can be built around these collections are worth examining.

Picking up on the historical narrative sketched by Stein, which identifies parallels between the US and Germany with regard to how comics were overlooked, if not outright rejected by institutions (28), Bernd Dolle-Weinkauff’s contribution critically examines the lack of comics in scholarly institutions in Germany. Throughout his chapter, Dolle-Weinkauff names several important resources and provides a helpful overview of the archives, libraries, and collections that do exist or are growing in Germany. He makes note of various projects to digitize historic comic collections and calls on the comics studies community to create a central open source database of these works: »[Es] wäre ein wichtiger erster Schritt, die in den einzelnen Datenbanken wissenschaftlicher Bibliotheken verstreuten Digitalisate zusammenzutragen und der Forschung in einem zentralen open source-Datenpool verfügbar zu machen.« (87) Dolle-Weinkauff’s chapter also provides crucial context by considering comics in relation to the 19th-century tradition of »Bildergeschichten« (74), and in discussing what qualifies as an »original,« the chapter links back to the volume’s overarching questions of archiving.

Building on Dolle-Weinkauff’s essay, as well as his previous research, Carola Pohlmann delves into the history, context, and contents of the comic collection in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (SBB; Berlin State Library). As director of the Kinder- und Jugendbuchabteilung (Children’s and Young Adult Book Section) of the SBB, Pohlmann is in a unique position to speak to how this collection was started in 2015 and then took off in 2018 thanks to a generous donation of American superhero comics that includes an emphasis on female comic book characters (e.g., Batgirl, Batwoman, Black Widow, Catwoman, Ms. Marvel, Red Sonja, She-Hulk, see p. 94). In addition to outlining the focus of the collection, Pohlmann also makes note of the library’s guidelines for future collecting and cataloging that also include the very important aspect of coordinating the work of the collection with public outreach efforts (93 and 95 f.).

Jaqueline Berndt’s contribution on manga archives in Japan is also a history of how private collections have developed into a national database. In the opening section of her essay, she provides a helpful characterization of comics studies in Japan, highlighting among other aspects the interest in gender-specific genres, fan culture, and issues of globalization (as opposed to the literary scholarship or sociological frameworks that are preferred in comics research in North America and Europe) as well as the Japanese Society for Comics Research that was founded in 2001 and that promotes data-driven studies over historical or theoretical approaches. Berndt’s chapter then takes a deep dive into the history, context, and contents of existing institutions and collections and how to access them – in person or digitally – highlighting in particular the Media Arts Database, an online catalog started in 2015 by the national ministry of culture. In addition to broadening the scope beyond North America and Europe, Berndt’s chapter expands on the aspects that need to be considered under the topic of comics and archive, showing the complexities both in terms of genre definitions and archival practices (cf. the examples of collecting original manuscripts, p. 101-102, or the discussion of the difficult to define term of »media art,« which includes animation, advertisements, video clips, and computer games, p. 105). As an appendix to her contribution, Berndt provides an incredibly useful list, based on Dalma Kálovics’ 2019 dissertation, of the most significant institutions (libraries, museums, and private collections) with archives specializing in manga (112-113).

In the last chapter of this volume, Stephan Packard takes stock of the current »Frühzeit« of digital comics. In particular, he sets out to explore how the transformation of comics’ mediality calls comics’ materiality into question, while also offering a »Praxeologie der Comiclektüre« (116). Building on the work of Adrienne Resha, Packard highlights how increased communication via social media raises new questions regarding the production and reception of comics. The digital comics considered here are not digitized versions in archives and libraries but rather the digital form offered by publishers alongside printed comics books. In this context, Packard examines in particular Comixology, the digital comic reading platform owned by Amazon. In exploring aspects like materiality, (inter)mediality, and reading practices, Packard draws attention to both »Technologie« and »Technik,« that is to the devices themselves and how readers engage with them, raising new questions about the relation between comics and archives. While digital comics may still be in an early age, the age of archiving digital comics is yet to begin, and a volume like the present one is an excellent starting point for charting the path forward.

This book will be of interest to comics scholars, archivists and librarians, and collectors with an interest in the broader context of their individual engagement with comics. It will be of particular use to students and scholars looking for an overview of both comics archives and practices of archiving comics. One desideratum: It would have been nice if the editors had included an overview list (similar to the appendix to Berndt’s chapter) of the most important comics collections, databases, and online resources that are referenced throughout the volume.

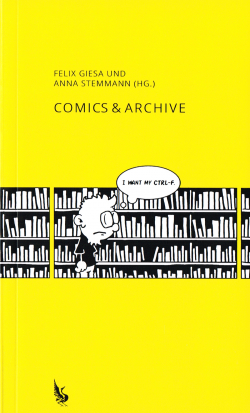

Comics & Archive

Felix Giesa and Anna Stemmann (Eds.)

Berlin: Christian A. Bachmann Verlag, 2021

132 pp., 10 Euro

ISBN: 978-3-96234-045-2